SECURITY AS A STATE OF VIOLENCE

- Woodblock Relief -

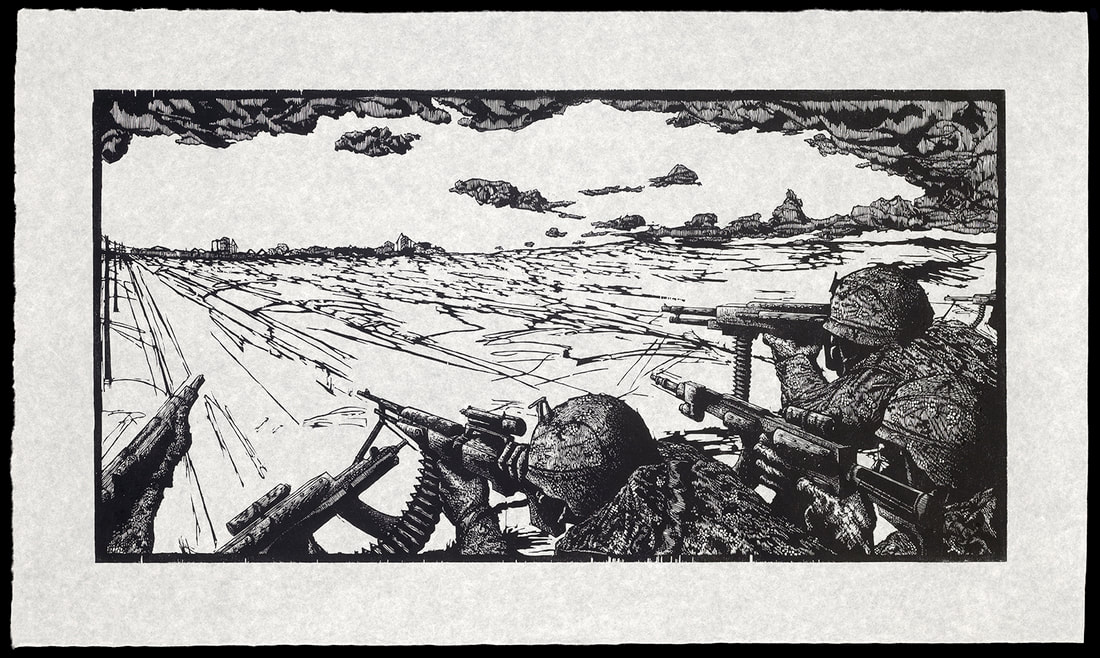

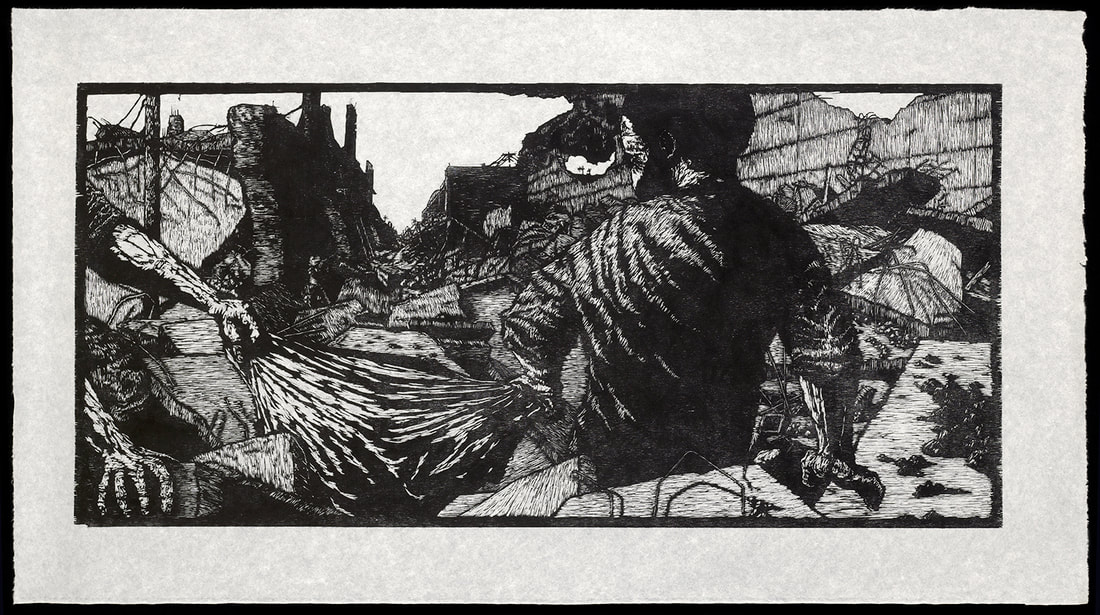

Security Blanket reveals the brutal reality of military, political, and economic policies: human and environmental horror wrought upon the globe. The security blanket is synonymous with body bags destined for unidentified mass graves. The blanket casts a wide and indifferent net, negating the humanity of those, at least in rhetoric, such interventions intend to help (or “save”). The gross detachment that modern warfare permits (and promotes) - through active suppression of information, persecution of whistleblowers, misinformation from news sources and the government, subcontracting of warfare, and increasingly remote tactics and battlegrounds - is one of its most toxic and psychologically damaging outcomes.

Security Blanket: Cottage Grove depicts the presence (actual, displaced, or threatened) of violence inherent to development. The print requires an expansive interpretation. It references a suburb of Saint Paul, MN and its recent conversion of farm land to suburban development in a rapid and dizzying proliferation of cul-de-sacs. Behind this lays the legacy of the settler colonial project, reified by the Northwest Ordinances of the 1780s which, in the act of attempting to erase Native life, first made the lands orthogonal. In this landscape, violence is layered upon violence, and each form begins with the myth of empty land. The past is consecutively erased through selective surveying, plowing under, washing downstream (into the Gulf's Dead Zone), and now large-scale paving over. Further, these "developments" contain contingencies of their own. Currently, the codification of the nuclear family and work commute direct extraction, militarism, and imperialism abroad (and increasingly domestically). Lastly, the print points of the contemporary sites (Palestine, Standing Rock, Wetʼsuwetʼen Territories, etc.) where development and the colonial outpost are still utilized as warfare tactics; where victimhood is inverted.

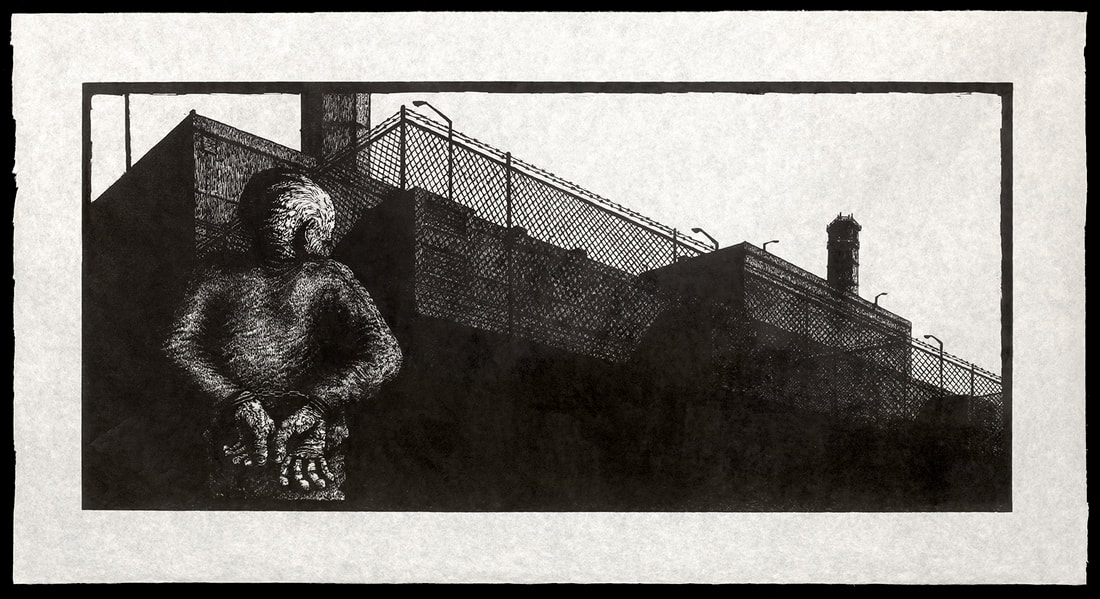

Silent Retreat congregates the multiple subjectivities created by incarceration. The title creates an uneasy tension between those able to explore spiritual and meditative practices, and those incarcerated, which is to say, those from whom the world has retreated. By placing the handcuffed being outside of the jail/prison walls, the viewer also apprehends the institution with hands restrained. These walls encourage isolation, they keep in those on the inside, and keep out those on the outside. A paradox then emerges; institutions create an infuriating world requiring retreat, while (privileged access to) retreat maintains and reproduces the carceral system of exclusion and inclusion.

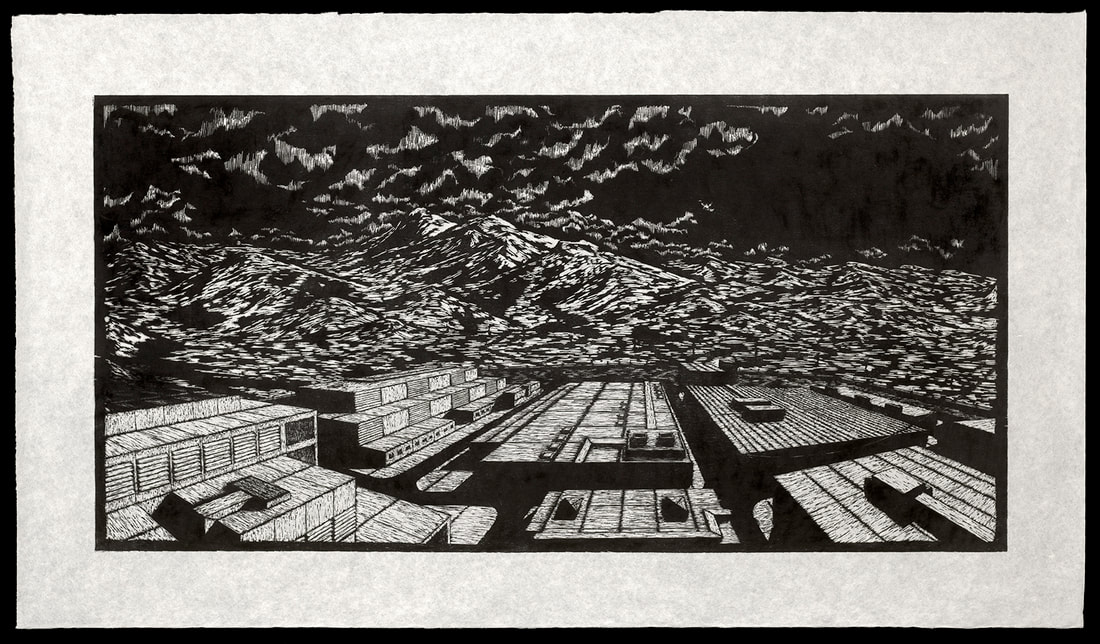

The Utah Data Center (code-named, Bumblehive - see Safariland: Capital's Menagerie for a discussion of the destruction and de/employment of Nature) is a National Security Agency (NSA) operated facility in Bluffdale, Utah. The one-million-square-foot, 1.5-billion-dollar site was completed in 2014 to expand the NSA's capacity to filter and store data, ranging from email correspondence, cell phone communication, financial transactions, and general "digital pocket litter." In addition to raising concerns of privacy, the site is emblematic of the ever-encroaching Euclidian landscape which interprets and transforms a formerly unpredictable world into one that is regular, gridded, and highly legible. The site demonstrates the illusory, fetishized nature of the cloud, as the virtual touches down on the landscape, excavating foothills, demanding rare-metals resources, and entrenching carbon intensive energy demands.

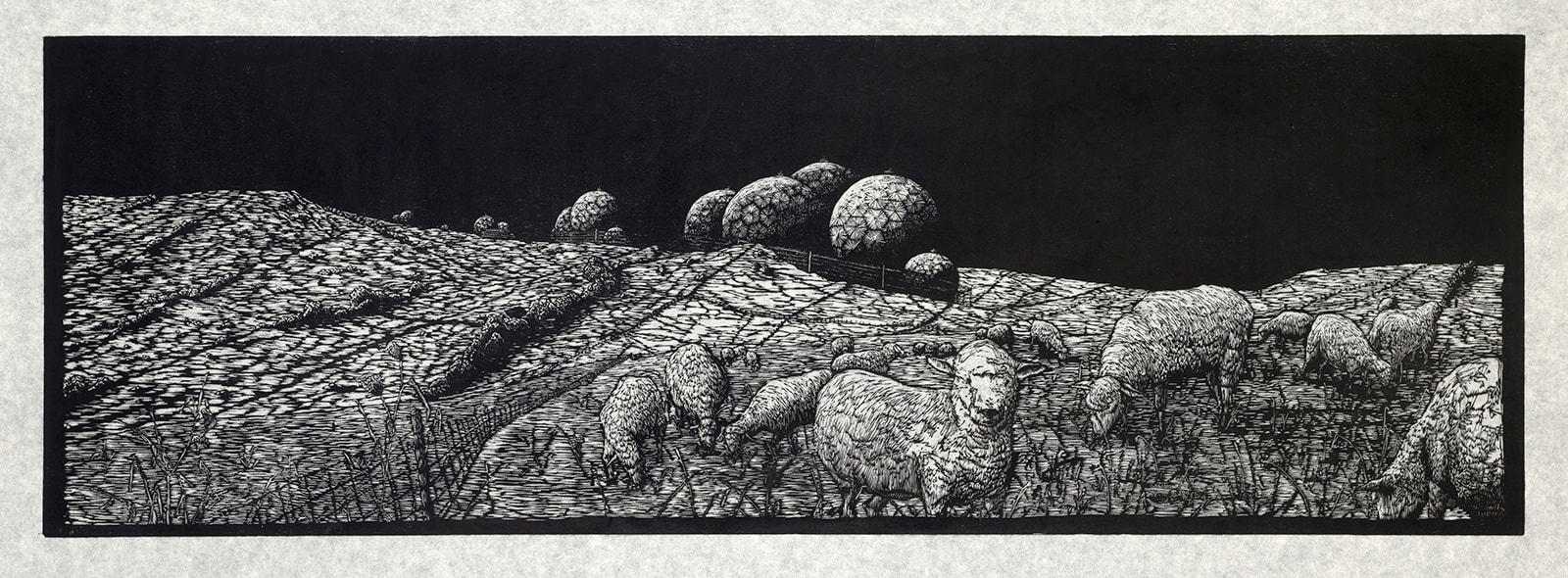

Menwith Hill is a National Security Agency-operated surveillance base, located in rural England. This site is part of a multinational constellation, Five Eyes (USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), which intercepts satellite signals and is a continuation of Anglophone global rule. Information gathered at Menwith Hill directs lethal drone strikes in North Africa. The rendering of Menwith Hill extends beyond locating digital technologies in physical geographies to make an argument concerning the long history of social control (which is to say the racial and spatial allotment of life and death) throughout time. Upon the bloody terrain of land enclosure, an emblematic origin of primitive accumulation and proletarianization, the same landscape again becomes a frontier of (neo)colonization, enclosure and warfare, now digital and racialized.

In concert with other prints, Child's (Re)Pose: Threshold of Detectability shows another facet of violence waged in and on the built environment and the invisibility (rather, erasure) of its human toll. Through obscuring the actual instance of death from the viewer, the print makes this unidentified life hyper-legible. The connection is intensified and mirrored by the tension holding the two actors. It asks the viewer to trace the material relations connecting the viewer and subject, not seeing the death as an isolated tragedy, but a direct outcome of simultaneous and co-constitutive modes of being. Further, the destroyed landscape is a harbinger of "development" to come. Modern warfare is seldom characterized by territorial gains, but rather the opening of "new" markets for multinational corporations waiting to proliferate. And thus, overtly violent conflict bleeds into a more insidious form cultural, social, and economic homogenization, which is to say genocide.

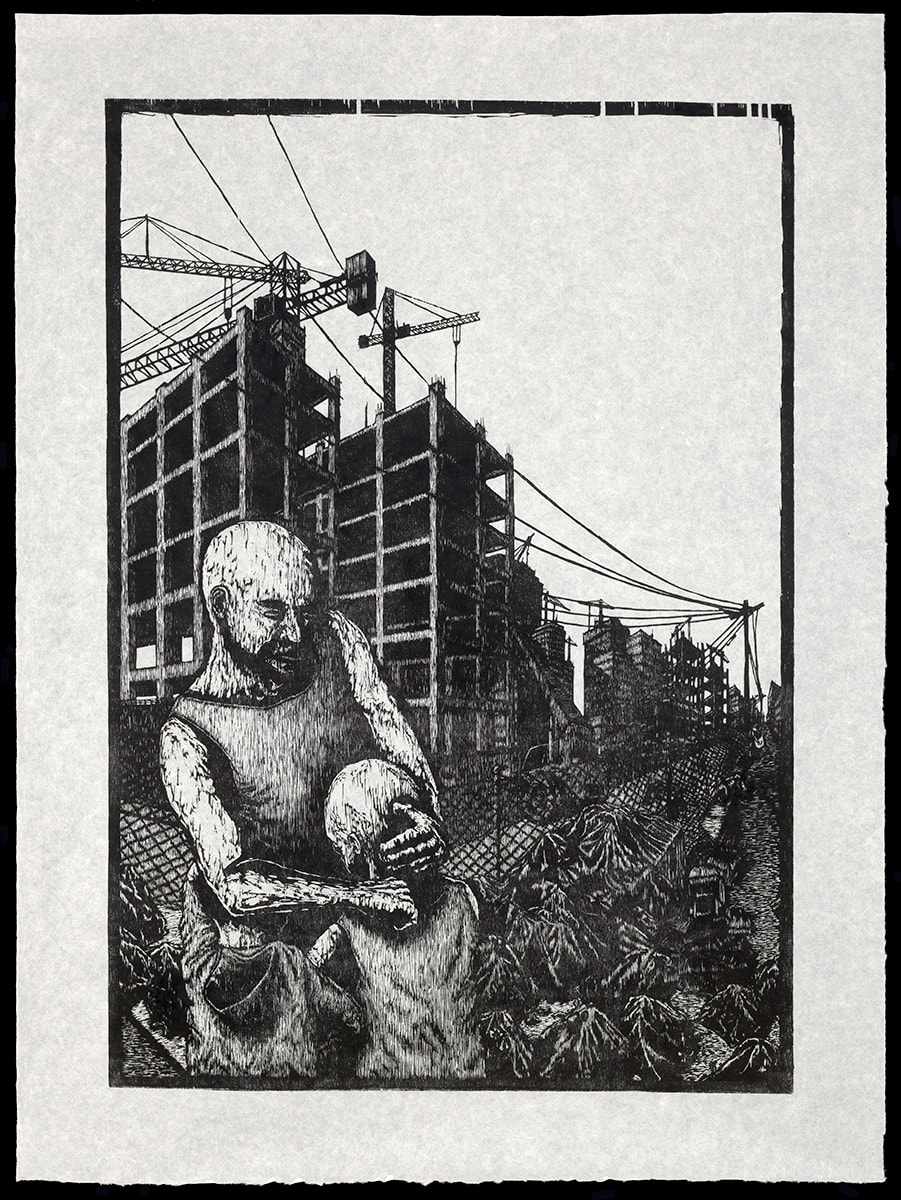

Child's (Re)Pose: No Totem is in reaction to Charles White's Birmingham Totem. Carved during reinvigorated Anti-Black violence - after three Church arsons in Louisiana, which were preceded by the Charlottesville, VA Unite the Right rally, and Dylann Roof's shooting in the Southern Emmanuel Church in Charleston, NC - No Totem questions the notion that "Progress" is possible, that rebuilding is imminent, and even whether art can serve social movements. Perhaps more than questioning Charles White, the print condemns the incorporation of radical liberatory struggles (or simply, the insistence of life) into the liberal paradigm of Progress or Rights. This paradigm signifies an impossible mode of politics: one reliant on a State for enforcement and validity, but also on a State built by the refused, for the refusers. Ultimately this manifests as a politics of denial, delay, and accumulating death.

Along with Security Blanket I-X and Safariland: Capital's Menagerie, the two prints entitled, Child's (Re)Pose, challenge the role of the Child in politics. The journal Baedan states, "the Child is the fantastic symbol for the eternal proliferation of class society." This society "ensures the sacrifice of all vital energy for the pure abstraction of [its] idealized continuation... a struggle for Life at the expense of life; for the Children at the expense of the lived experiences of actual children." The two prints also criticize the (neo)liberal infatuation with atomized "self care," demonstrating the distorted notion of a "self" that can be cared for in absentia of other beings and material relations. It rejects the false equation of health with morality, and shows how, in actuality, those "healthy" lives are predicated on distanced and devastating extraction and oppression.

Along with Security Blanket I-X and Safariland: Capital's Menagerie, the two prints entitled, Child's (Re)Pose, challenge the role of the Child in politics. The journal Baedan states, "the Child is the fantastic symbol for the eternal proliferation of class society." This society "ensures the sacrifice of all vital energy for the pure abstraction of [its] idealized continuation... a struggle for Life at the expense of life; for the Children at the expense of the lived experiences of actual children." The two prints also criticize the (neo)liberal infatuation with atomized "self care," demonstrating the distorted notion of a "self" that can be cared for in absentia of other beings and material relations. It rejects the false equation of health with morality, and shows how, in actuality, those "healthy" lives are predicated on distanced and devastating extraction and oppression.

Kickstarter highlights the contradiction of the modern urbanization movement, where building is entirely detached from need and financial speculation is a reason for construction unto itself. As urbanization and real estate domination reach an apogee, the disparities of city dwelling and the violent, cyclical mechanisms of gentrification (disinvestment, speculation, destruction, renewal) are ever more apparent. In an oblique reference, the print also points to Li Hua's prints, Fleeing Refugees, suggesting that displacement is often a manufactured crisis tied to the built environment. The title also condemns the transference (outsourcings, individualizing, and decontextualizing) of responsibility that online crowdsourcing platforms enable and the way in which they profit from individuals' misery due to society's inability to adequately provide for basic human necessities.

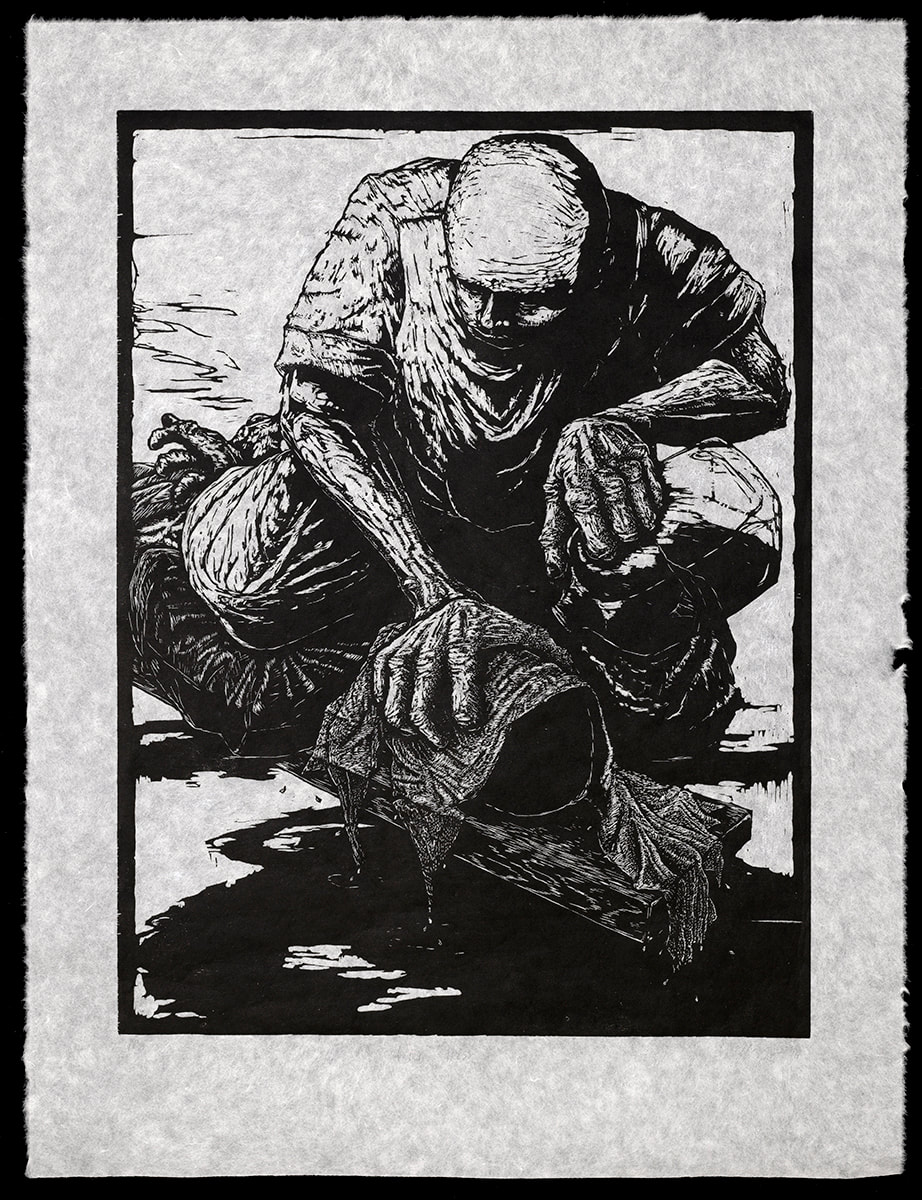

Embedded Reporting: Nightmare III illustrates the brutal, intimate technique of waterboarding, in contrast to other remote tactics of warfare and enforcement of hegemony. The suppression of journalists and the press (internally and externally) serves as yet another method to distance the techniques of enforcing control with those who enjoy its splendors. While increasing technology characterizes the trajectory of modern warfare towards the more remote, intimate forms of domination, torture, and violence persist. Their persistence reveals that they are just as integral (or perhaps more so) to warfare and that battles for cultural and personal domination are inherent and constitutive to military actions. Formally, the print references Nightmare II, a print by Zhao Yannian who was persecuted during China's Cultural Revolution.

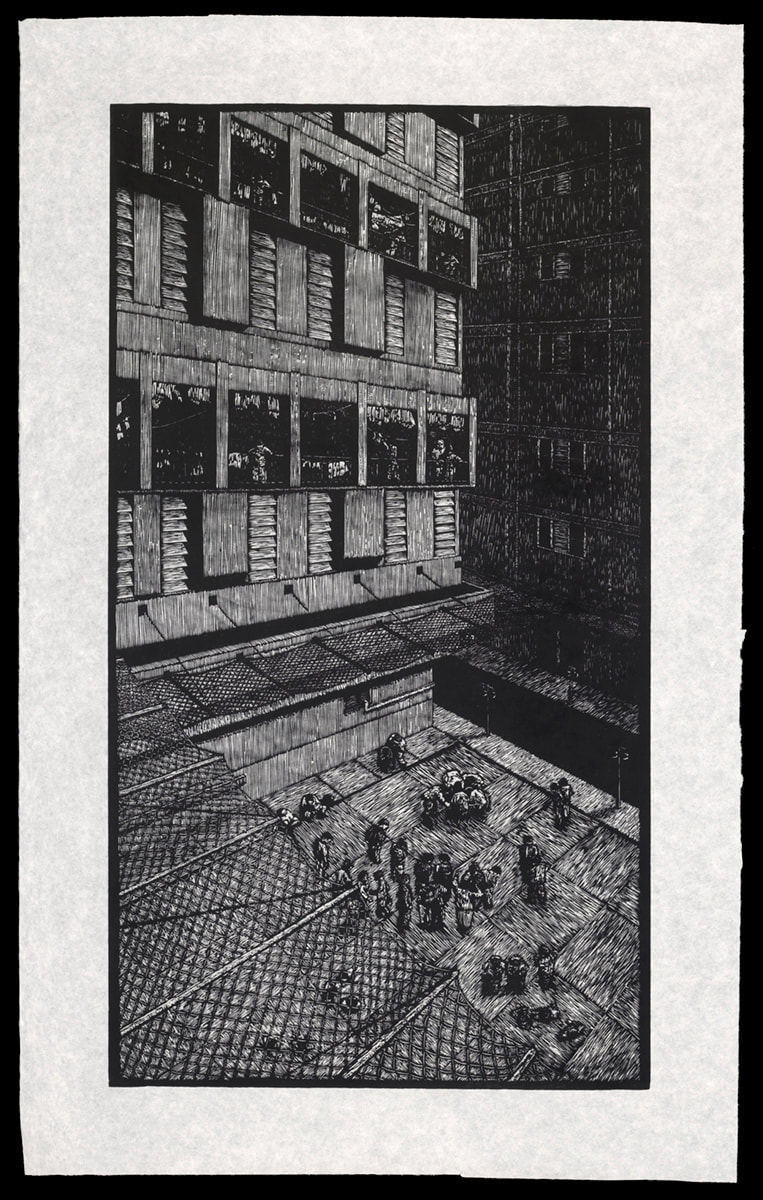

Safe Space: Foxconn targets the emptiness of non-structural change in ameliorating contemporary alienation, poor mental health, and employment conditions. It references the spate of suicides and suicide attempts at Foxconn, a factory of high-tech electronics based in China, in the years surrounding 2010. Instead of addressing the dire working conditions – poor pay, a six-and-a-half day workweek, deskilled and repetitive tasks, etc. - the plant merely installed safety nets to catch workers who decided to jump. Foxconn, a tightly secured, monolithic, expansive “campus” (and the iPhone with its sleek modern design bereft of any sign of labor process) also embodies the intentionally created abyss between producer and consumer, object and production. The print not only remembers those who took their lives in Shenzhen, but cautions viewers in the United States, as Foxconn is developing a campus in Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin, an endeavor already riddled with large subsidies, property seizures, unmet goals of costs, employment, and timelines, and evasion of safety precautions.

The print also evokes the campus movements, sexual assault awareness, and the reinvigoration of Black politics that have animated a contemporary debate over the idea of “safe spaces.” Contemporary political movements have demanded the creation of safe spaces – time and place apart for healing, reflecting, organizing, and planning. In these spaces, communities are created and supported, critical discussions occur, and actions are orchestrated. However, the notion of a “safe space” is inadequate. Zeus Leonardo writes, “race dialogue is almost never safe for people of color in mixed- racial company. But before we romanticize its opposite, or same-race dialogues, the idea that homogeneous spaces are automatically safe for people of color is a mystification (confusion); for, that kind of “safe space” results precisely from a violent condition: racial segregation.” And to illustrate the brittleness of the term, prominent neo-Nazi, alt-right leader Richard Spencer imagines the United States of America to be. “…a safe space effectively for Europeans…a big empire that would accept all Europeans. It would be a place for Germans. It would be a place for Slavs. It would be a place for Celts. It would be a place for white Americans and so on.” "Safe space" is a vacuous term. Lacking context, it invites its own undermining, perversion, and cooptation. Terms better stated to emphasize the relationship to power are the “crawl space” articulated by Jay Gillen or the “undercommons,” coined by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten.

----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- -----

- Leonardo, Zeus. “The Problematics of Safe-Space Dialogue.” Pedagogy of Fear: toward a Fanonian theory of safety in race dialogue. ASDIC Metamorphosis, 2015.

- Richard, Spencer. Interview with Kelly McEvers. “We're Not Going Away': Alt-Right Leader On Voice In Trump Administration.” NPR, November 17, 2016

The print also evokes the campus movements, sexual assault awareness, and the reinvigoration of Black politics that have animated a contemporary debate over the idea of “safe spaces.” Contemporary political movements have demanded the creation of safe spaces – time and place apart for healing, reflecting, organizing, and planning. In these spaces, communities are created and supported, critical discussions occur, and actions are orchestrated. However, the notion of a “safe space” is inadequate. Zeus Leonardo writes, “race dialogue is almost never safe for people of color in mixed- racial company. But before we romanticize its opposite, or same-race dialogues, the idea that homogeneous spaces are automatically safe for people of color is a mystification (confusion); for, that kind of “safe space” results precisely from a violent condition: racial segregation.” And to illustrate the brittleness of the term, prominent neo-Nazi, alt-right leader Richard Spencer imagines the United States of America to be. “…a safe space effectively for Europeans…a big empire that would accept all Europeans. It would be a place for Germans. It would be a place for Slavs. It would be a place for Celts. It would be a place for white Americans and so on.” "Safe space" is a vacuous term. Lacking context, it invites its own undermining, perversion, and cooptation. Terms better stated to emphasize the relationship to power are the “crawl space” articulated by Jay Gillen or the “undercommons,” coined by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten.

----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- -----

- Leonardo, Zeus. “The Problematics of Safe-Space Dialogue.” Pedagogy of Fear: toward a Fanonian theory of safety in race dialogue. ASDIC Metamorphosis, 2015.

- Richard, Spencer. Interview with Kelly McEvers. “We're Not Going Away': Alt-Right Leader On Voice In Trump Administration.” NPR, November 17, 2016